In October I came across an article on ArsTechnica about a kickstarter for a 1,200 page, two volume book chronicling the history of keyboards. While I had never previously been interested in the history of this device I use every day, I’m still a retro computing enthusiast and was naturally intrigued. After reviewing the campaign and looking at the beautiful book I immediately said “take my money” and bought it as well a bonus pamphlet about the history of the return and enter keys. In reality, the title alone, Shift Happens, was enough to convince me to buy.

The author of the book, Marcin Wichary, started the project in 2016 and launched it in March 2023. I ordered in October and received the book in early December. Throughout the short waiting period, Wichary provided frequent updates about the progress of the book, chronicling its printing (in Lewiston, Maine, no less), slipcase issues, packaging woes, and shipping. As the shipping date moved ever closer to Christmas he even released a poll asking who really needed it by the holiday and who didn’t. I said I didn’t need it but preferred it and ended up getting in on one of the first shipments.

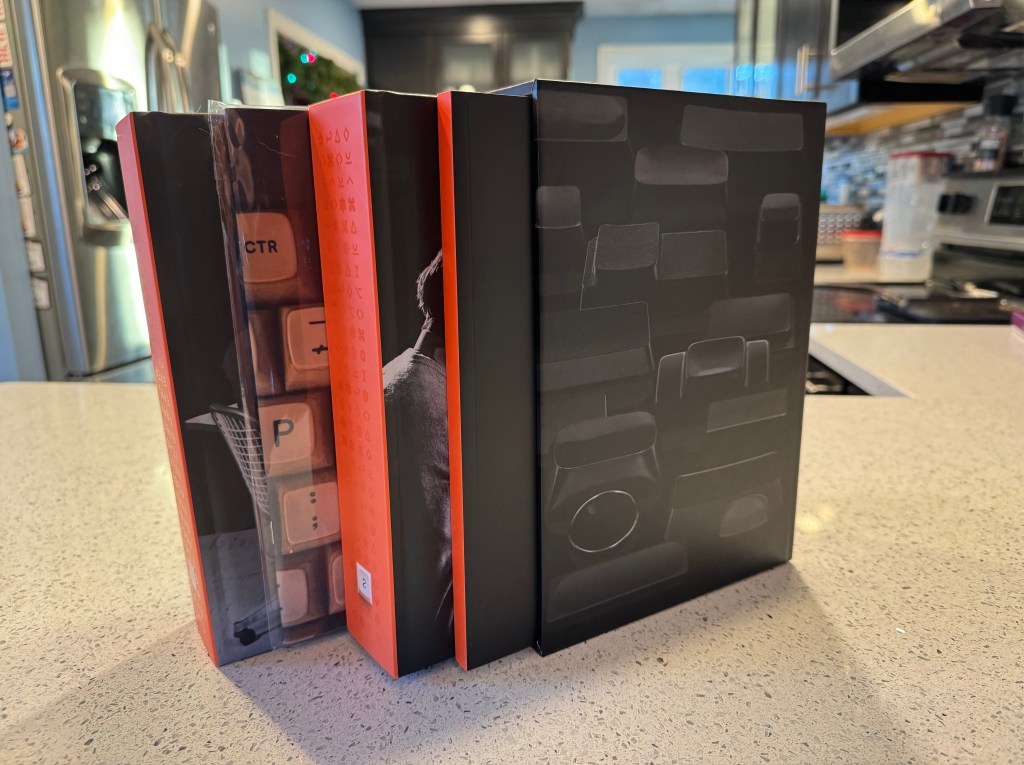

It arrived in a large, heavily padded box in perfect condition. Upon opening it, all I had to say was what an impressive book set. The slipcase is really beautiful, in deep black with dark image of blank keycaps wrapping around the sides and back. The case contrasts with the vibrant orange binding of the two hard cover and one soft cover volumes. It isn’t noticeable at first, but the bindings are embossed with clear characters that catch the light at different angles – a nice touch. The main books are numbered 1 and 2, on images of keycaps, of course. The books themselves are sturdy, with thick covers and beautiful black and white images on the front and back. There’s no stupid dust jacket to slip off or rip either – just a solid, well-made cover. The inside of the books is high quality as well, with thick paper and a matte texture. I initially wished the texture was more glossy to enhance the contrast of the 1300 images, but came to appreciate the reduced glare of the matte pages as I read.

While I wasn’t familiar with the history of keyboards I am familiar with keyboards. I own a small collection of vintage keyboards, mostly Apple – the original mechanicals (Apple II, IIc, the original Macintosh, the first ADB, the famous Apple Extended and Extended II), the crappy membranes (Apple Design, early PowerBooks), the early USBs (G3 iMac, Pro), the late Powerbooks, the Aluminum Powerbooks, up through Apple’s current Magic Keyboards. I know how they relate to each other, but I had no idea where their layouts came from, why they are arranged they are, and how much history shaped them. I never thought about it until I read this book.

Shift Happens is fascinating and the love and enthusiasm put into it is evident. Wichary sets the foundation by introducing all of the predecessors that make keyboards what they are today and then shows how computer keyboards evolved from there. The first volume focuses on typewriters and how they evolved into teletypes, electrics, and eventually computer terminals. There are interesting chapters about the defacto QWERTY keyboard layout, its terrible internationalization, how shift came to be, and how women were the main and least appreciated users of typewriters.

The second book dives into personal computer keyboards with chapters chronicling famous designs from IBM, mechanical switches, terrible membranes, ergonomics, electronic word processing typewriters, control keys, international support, kanji, emoji, and the transition to smart phones. It details how function and control keys migrated around the keyboard from their places on mainframes and early computers.

The two volumes are divided into many chapters, usually starting with a story about keyboard history from a different perspective and tying it into previous content by the end. There are lots and lots of great images throughout with keyboards, typewriters, computers, ads, and clippings from manuals. It’s really engaging and interesting to read.

I read most of the book over my holiday break and enjoyed it all. Throughout my reading I came to be interested in the transition from typewriting to computing in the form of electronic typewriters. These are basically slow computers attached to a printer that immediately print each character typed. I also came to re-discover mechanical keyboards, which I’ve dabbled in before through my retro computing collection.

There is simply too much content packed into these books to summarize it all, so I’ll leave you with some of the interesting things I learned along the way.

- The first typewriters typed on the back of the page – it wasn’t until years later that typists could actually see what they typed in front of them

- Many typewriters had limited symbols, instead requiring multiple characters to by typed on top of one another. Want a dollar sign? Type an S, backspace, and then type an l. Or just mark it yourself with a pen. They also didn’t have keys for the zero or one digits. An uppercase O or a lowercase l would do.

- Typewriters actually didn’t have lower case letters for years either. What looks like yelling today, was the only way to type back then.

- In fact, the terms lower and upper case come from the printing press of the 1400’s, where the metal letters were stored in cases on shelves, the capitals in the “upper” case and the others in the “lower” case.

- It took a long time for keyboard layouts to settle down and for the concept of the shift key to form. Some typewriters had no shift keys, instead opting for separate keys for lower case and upper case letters. Some had additional keys for symbols as well. Some used one shift key to shift between cases, others used two shift keys to shift between cases and then between letters and symbols. The second variation is similar to how a smartphone keyboard works today.

- The QWERTY keyboard layout was indeed designed to reduce the possibility of type bars smashing into each other. There were other layouts, but QWERTY became a defacto standard and influenced some truly horrible “internationalizations” that slowed typewriter adoption in other countries or influenced their written language with its limitations. Fun fact: QWERTY allows you to type the word “typewriter” without moving your fingers from the top row 🙂

- Electric typewriters existed in the 1920’s. They were electric in that a motor spun a shaft that would smack the type bar against the ink ribbon and paper after a light touch from the operator, similar to electronically assisted steering and braking in cars. Electric and manual typewriters coexisted up through the eighties.

- Criminals loved typewriters because their handwriting couldn’t be traced from them

- Typewriters made it easier and faster to write documents and could even make up to 20 copies at a time with enough layers of carbon paper, but any mistakes were duplicated as well. Early computers allowed instant editing and unlimited copies but were so unreliable and unintuitive that an entire document, manuscript, or book could be irrevocably lost in an instant. Many writers avoided computers for many years for this reason.

- IBM took over the typewriter industry in the sixties with the introduction of its Selectric, which had no carriage to return and used a ball instead of type bars. You may remember it from Mad Men. The result was a typewriter that was faster than anything on the market and didn’t jam. The Selectric represents the last major design of mechanical typewriters and eventually captured 75% of the typewriter market.

- The Selectric was used as a terminal for mainframes and was eventually sold with a memory disk that could store and replay (i.e. reprint) documents without the need for carbon paper

- IBM’s 1970’s Beam Spring keyboards used springs and solenoids to replicate the feel of the Selectric. This mechanism was expensive and was replaced later in the decade with the buckling spring, which attempted to create a similar feel. These are still considered some of the best typing keyboards of all time.

- The control and escape keys, used in the command line Vim and Emacs editors, were originally located in easier to reach places on the keyboard, which explains why they are so prominent in these applications. On my 1988 Apple Desktop Bus keyboard, the control key is located where Caps Lock usually is goes, making it much easier to hit.

- Speaking of the control key, its concept originated on teletypes from the early 20th century. Teletypes were basically two typewriters in different physical locations connected remotely. The user typed on one, which converted key presses in to signals sent over a wire. Control characters were introduced to represent non-printing keys like backspace and return. The control sequence for backspace is ctrl-H, which still works in many operating systems today, including Mac OS Sonoma.

- Early ergonomic keyboards from Apple and Microsoft were criticized for not being radical enough; they were deliberately conservative to ensure people would actually buy them

- Mavis Beacon is one of the most recognizable Black women from 80s and 90s technology. She’s not even a real person.

- There was a version of the arcade game House of the Dead for typing. It was called Typing of the Dead (no joke), had two keyboards, and required you to type things like “Asbestos Soup” and “Legwarmers” to fend off zombies, who coincidentally, were carrying keyboards

- Early predictive-text programs were used in the 80’s to enable people to type the thousands of Japanese characters that couldn’t fit on a keyboard. The user typed in hiragana, which is syllabic, and the program provided a list of options to represent the actual word.

- The 2005 Optimus Maximus keyboard gave us an idea of what phones would later perfect. On the Maximus, every key was a tiny screen that could change depending on what you were doing. In practice it was difficult to use, the flat key caps making it uncomfortable and your fingers obscuring the view what was on the key. Smartphones did this better. Apple introduced a similar concept with its Touch Bar in 2016 and it fizzled and died as well.

- Stenographers can type super fast because they type in a specialized short hand. Before computers, they used typewriters and would have to convert the shorthand to words after. Now computers translate it in real time. Pre-conversion, some of it looks like words, but much of it looks alien.

- The first emoticons were invented on the PLATO educational computer in 1972. PLATO allowed users to backspace and type characters on top of other characters (like a typewriter). By typing characters over one another, you could create images. For instance, O$* created a smiley face and O$>< created a frown. Emoji as we know it today, came from Japan in 1999.

- Women were marginalized throughout the keyboard’s history. In the typewriter era, the vast majority of typists were women because typing was considered “mechanical work”. Men would do the thinking and dictate the ideas, women would write them down. There were even cringey 1950’s pamphlets about how being a great secretary meant “hiding your light” by allowing your (male) boss to take credit for your ideas. In addition to typing the amazing ideas men came up with, women also made up the vast majority of the data input workforce, entering census data on punch cards, for example. In the computing era they did “mechanical” work again, this time writing programs (specced by men) onto punch cards to be run by computers. Once men realized that the act of programming was more creative than mechanical, programming shifted to a male-dominated profession. Growing up outside of that era, I find that history very disappointing.

2 Replies to “A Story of Keyboards”