I’ve had success installing both CF-to-IDE adapters and 2.5″ SSD-to-IDE drives in my older computers, but those only cover about ⅔ of my collection. The rest of my machines, Macs from the late ’80s and early ’90s, don’t use IDE at all; they use SCSI – an older and more expensive interface. Replacing SCSI drives is challenging: they are difficult to find and usually cost over $50 each. But like my IDE solution, there are also solutions for SCSI, one of which is called BlueSCSI.

All About BlueSCSI

SCSI has always been complex and expensive, even in its heyday. As such, BlueSCSI requires a microcontroller rather than simple passthrough circuits, which makes it more expensive than its IDE counterparts. The pricing ranges from $30 – $50 assembled, which is 2-3x the cost of a similar CF-to-IDE or SSD-to-IDE adapter, but cheaper than many real SCSI drives you’ll find and far more flexible.

There are two versions: one based on Arduino, and one built on Raspberry Pi. Each are open source designs and work in a similar way, with the Raspberry Pi version offering enhanced performance and a few additional features. They both use SD cards to store disk images that act as SCSI devices. BlueSCSI embraces the community aspect of its open source design and isn’t available centrally, instead being federated out to community members who sell the boards to assemble (i.e. solder) yourself or provide pre-assembled versions for an additional fee. You won’t find these on Amazon.

BlueSCSI are available in multiple form factors – a 2.5″ size that takes a micro SD card, a 3.5″ size that takes a full SD card, and an external DB-25 version that takes a micro SD card. This is really nice because it provides a lot of flexibility: move the DB-25 version from computer to computer to transfer files or use for troubleshooting; install the 2.5″ or 3.5″ version for permanent housing in an old Mac.

The biggest difference between BlueSCSI and the SSD and CF adapters relates to how the SD cards are used. On an IDE adapter, the CF card or SSD is treated as a single device. It appears to the OS as a single piece of hardware and is formatted or partitioned as if it were a single physical drive. BlueSCSI represents multiple devices through disk image files stored on the SD card. The images are named to represent their ID on the SCSI bus, meaning that one BlueSCSI can represent up to 7 SCSI devices. Each disk image appears to the OS as a separate device and can be formatted or partitioned. BlueSCSI v2 can even emulate CDs! This works much the same way as a Floppy Emu does for emulating an Apple II or Macintosh floppy drive.

The advantage of using disk images is that it’s easy to put pre-configured OS and software installations on the card or copy them around without waiting for a full install to complete on every machine its used with. This is not only faster, but can help if you have a machine that doesn’t have a working floppy drive or CD-ROM drive for installation.

My BlueSCSI

There are two major versions of BlueSCSI – the original and version 2.0. Both have the same compatibility, come in the same configurations, and use the same file structure. The v2 models use a Raspberry Pi which improves their transfer speeds and allows them to do nifty things like provide WiFi (yes) to old machines, copy files to / from the SD card directly, or even make bit level copies of SCSI disks without a computer at all.

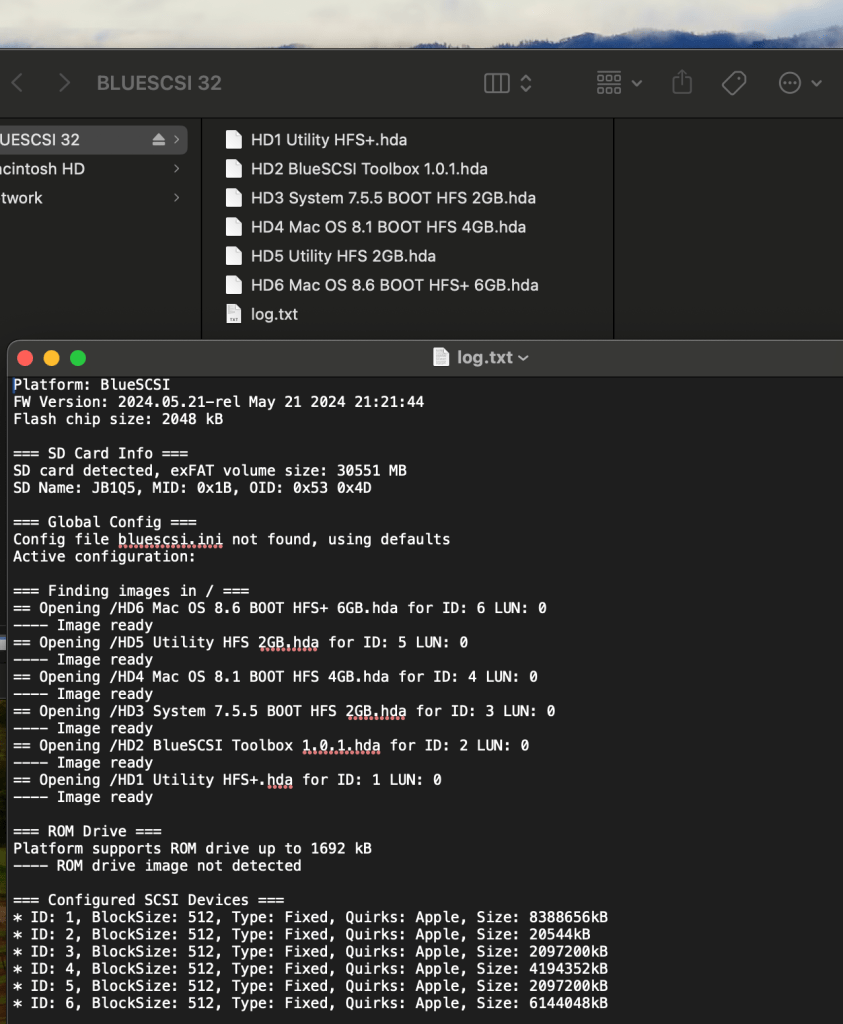

I own both versions. I bought a couple V1s several years ago, but thought they were complicated at the time and didn’t have a burning use case, so into a drawer they went. I read about the V2 recently and it reignited my interesest, so I of course bought a few of those. I set up the external DB-25 version since I can move it from Mac to Mac easily. Setting up the files was far less intimidating than I thought – I used Disk Jockey which conveniently created the images, installed hard disk drivers, and named the files so BlueSCSI would see them. I created 7 images of different sizes, dropped them on the SD card, popped it into the BlueSCSI, plugged it into a PowerBook G3 PDQ, booted, and formatted each one as it was recognized as a new volume. It worked on the first try, so I guess it wasn’t so complicated after all!

I planned to use one card to boot multiple generations of Macs, so I installed System 7.5.5 on an HFS image, Mac OS 8.1 an an HFS+ image, and Mac OS 8.6 on another HFS+ image. I used an additional image as an HFS utility drive for System 7.5.5 and another as an HFS+ utility drive for Mac OS 8.1/8.6.

In theory having three bootable operating systems would work great as I thought that the machine would skip operating systems it couldn’t boot. But silly me, since the drives are bootable the Mac will attempt to boot the first one it finds and will error out if it can’t run the OS on that drive. After having no luck using shortcut keys to “force” a boot from a specific SCSI device, 1I gave up and moved the OS image I needed to SCSI ID 7 so it would boot first. That’s a temporary fix, so I may need to format a few SD cards, each with an OS for a given machine generation.

A note about SD cards

SD cards, like CF cards and SSDs, store data differently than a hard disk or floppy disk. Their design ultimately limits the number of times that their bits can be rewritten, eventually locking all of the data and causing software failures. Just as I looked for industrial-rated CF cards for my CF-to-IDE adapter, I had to look for “high endurance” cards for BlueSCSI that withstand a high number of write cycles.

I picked up two Samsung Pro Endurance cards, which are specially designed for use cases that rewrite data often, like dash and security cameras. They are micro SD cards but come with a full size adapter, making them easy to use in any of the BlueSCSI configurations. They aren’t super expensive either: I bought two 32 GB cards for $14.25 each in August and four more 256 GB versions for $23 each on sale during Prime Day in October.

Fragmentation

Since BlueSCSI is a microcontroller running software, it can do useful things like write a log file. When loaded, BlueSCSI creates a log on the SD card listing the status of each disk image, including a peculiar one that I ignored at first:

file is fragmented, see https://github.com/BlueSCSI/BlueSCSI-v2/wiki/Image-File-FragmentationI didn’t think much of it until upgrading the Mac OS 8.5 image to 8.6 and suddenly needing a full five minutes to boot. After the upgrade everything was slow, even drawing the menus! I was puzzled as Mac OS 8.6 is known to be faster than 8.5 and is a minor update I’ve installed probably 100 times now with zero negative effects.

After recalling the error and going to the site, I learned that extreme performance problems can occur if the SD card is fragmented. Not files within the disk image file, but the actual disk image file on the SD card. It basically means that the disk image data is strewn about the SD card, making it extremely slow to access. To remediate this, the contents of the card need to be copied off, the entire card deleted, and the contents copied back over one file at a time. The first time I did it I just copied all files back on at once and still had fragmentation. I literally had to copy one file at a time before the error disappeared.

I knew I succeeded because my next boot was fast like I expected it to be.

Performance

While BlueSCSI uses flash memory, its purpose is to make it easier and more economical to replace failing SCSI devices. Delivering performance improvements isn’t the goal, as in many cases, the computers are so old that their SCSI interfaces won’t show any improvement from solid state memory anyway. That’s borne out by some tests I ran using MacBench 5 on my PowerBook G3 PDQ from 1998. The internal CF Card I installed in it delivers up to 14 MB/s read performance, which is noticeable across the entire system from booting, to launching applications, and even displaying menus. BlueSCSI, on the other hand, delivers about 3 MB/s, which is a limitation of the speed of the external SCSI port. It’s rated to 5 MB/s, but that’s difficult to achieve. It feels more like a spinning hard drive, but it still works just fine.

A Great Buy, With More to Come

So BlueSCSI, at least on a Mac with a newer ATA interface, isn’t about performance, but it is about utility. It’s very convenient to have a device that can move from Mac to Mac for troubleshooting, testing, or can be mounted permanently. I can use it on Macs from 1986 – about 1999 to shuffle files around. I haven’t tried the internal versions yet, compared my v2 to my v1 hardware, or tried fancy features like “wifi”. At this point I’ve got two external devices that I can plug in to the backs of Macs and three internal ones I can use to replace dead drives. There’s more to cover but I’ve explored the most important and practical part of BlueSCSI, replicating a SCSI drive, and it works incredibly well. It was easier to setup than I expected and I plan to use it to keep some of my old Macs running. BlueSCSI is a winner.

- That might be a bug or limitation in the BlueSCSI firmware. I haven’t checked. ↩︎